Resource Library

U.S. Marketers Think Again About Emerging Markets

By Craig Charney | American Marketing Association | August 20, 2015 | 2 pages

Here are some things that everybody knows about emerging markets: The BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) are the markets of the future; China is the biggest draw for American marketers; and U.S. firms are charging into emerging markets.

Or, at least, that’s what everybody thinks that they know about emerging markets. A recent study by the New York AMA came to different conclusions.

The NYAMA’s Emerging Markets Attractiveness Survey discovered that marketers are now targeting the ICBM countries (India, China, Brazil and Mexico); Colombia has displaced China as the most attractive new destination for big firms; and most U.S. companies aren’t going into any emerging markets this year.

How American marketers see emerging markets matters for your bottom line. Your competitors are shifting their aim or, in some cases, holding back altogether. Companies that don’t keep up with the changes or that ignore neglected openings risk shrinking returns or missing profitable opportunities.

In January, I collaborated with Don Sexton, past president of the NYAMA, to conduct an online poll of 315 senior marketers at U.S.-based firms selling in global markets, fielded by Plano, Texas-based online market research firm Research Now. Half of the respondents are brand owners in a variety of industries, and half are at agencies (marketing, branding or advertising). Our report is out and it shows their insights are surprising, and valuable.

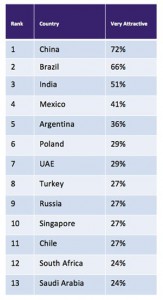

Figure 1: ICBM, Not BRICS Percent considering each market very attractive

Drop the BRICS, Launch the ICBM

We learned that the BRICS are a thing of the past for American marketers. That grouping, coined by Jim O’Neill in 2001, looks distinctly dated. Russia, hammered by sanctions and oil price drops, is down to No. 9 on our list of the 26 most attractive markets. (See Figure 1.) South Africa, plagued by years of low investment and mediocre growth, is No.12.

The top scorers on our “attractiveness index” are India, China, Brazil and Mexico. The rest of the top 10 are medium-sized, fairly successful countries—Argentina (No. 5), Poland (No. 6) and Turkey (No. 8)—or small but rich ones, such as the United Arab Emirates and Singapore.

Frontier markets—newer, less familiar emerging markets—draw much less interest. Of the 11 that we asked about, 10—all but Argentina—fall in the bottom half of the index. On average, 33% of marketers consider the more established emerging markets to be very attractive, compared with just 14% for the frontier markets. Despite the high growth and untapped markets that many offer, for American marketers, the frontiers are too wild.

Bogota: The New Beijing?

When we broke down where companies are going by their size, we got another surprise: Latin America is in the lead for large companies. The top target market for big firms (more than $10 billion in sales) to enter this year is Colombia, while Brazil is No. 2 and Chile is No. 4.

Colombia offers strong growth, a medium-sized market and a tantalizing prospect of peace after decades of internal conflict. Brazil, always the “country of the future,” is seen as having finally arrived, despite slower growth. Chile is South America’s success story, the likeliest country to enter the developed world.

Much of the entry strategy at work involves filling in gaps. With roughly 90% of the big firms already in China or India, the majority of new markets that they intend to enter are places where the American presence is comparatively weak. This is why Latin America is the most attractive region for big companies, followed by the Middle East.

However, small firms (under $100 million in sales) are piling into the ICBM countries. Only 40 to 50% are there now, and fewer still are elsewhere. Their global footprint is much smaller than that of big companies, so they are trying to catch up, with the Asia-Pacific region their chief destination. In fact, smaller firms are the most vigorous globalizers of all. More than three-fifths plan to enter new emerging markets in 2015.

Yankee, Stay Home

In contrast, just one-third of big firms and two-fifths of medium-sized ones (with $100 million to $1 billion in sales) will break new ground. This may reflect, in part, the head start in globalization that bigger firms enjoy.

What this means, though, is that the majority of U.S. marketers we surveyed are hitting “pause” on globalization: 55% say that their firms will not enter a single new emerging market in 2015.

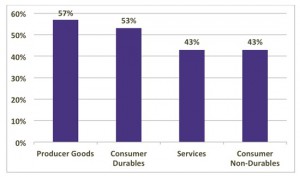

Figure 2: Capital Goods, Consumer Durables Lead the Charge Proportion planning to enter one or more new emerging markets in 2015

Yet there are big differences by sector (see Figure 2). The strongest push abroad is from intermediate or producer goods makers: 57% will enter emerging markets this year. Next come consumer durables producers, with 53% planning to test new markets. As companies in developing countries invest and their middle classes expand, American marketers are taking notice. On the other hand, services firms and consumer non-durables are moving more slowly: Only 43% of each are going into new markets.

Marketers seem to be missing the opportunities in one region in particular: Africa. It contains some of the world’s highest-growth economies and big potential markets, and few American firms are there. But not a single big U.S. firm in our study is going into Nigeria, Africa’s largest market (2014 growth: 6%), or Kenya (2014 growth: 5%). Only South Africa’s established market has pulling power, with 9% of big firms planning to enter. Have American marketers run up the white flag in the rest of Africa?

Indeed, the poll suggests that American marketers are hesitating about emerging markets in general, amid reports that their growth is slowing. Herd instincts are strong. The neglect concerns not just Africa, but other frontier markets. Reluctance is most notable among big consumer product and services firms. But the short term is not the only one, and there are risks in being behind the curve in the developing world. “Many firms are ignoring opportunities presented by global markets,” says Sexton, who also is a marketing professor at Columbia Business School. “They are leaving money on the table.”